Building a digital product follows certain steps in endless cycles. Inspiration, idea, concept, test, change, release, sell, analysis, growth, iteration.

One of the mantras repeated time and time again is to follow a principle of 80/20 to achieve the most important results fast, while only relying on limited resources.

Wilfredo Pareto first observed and formalized the 80/20 principle, stating that 80% of the effect comes from 20% of the causes. The rule can be commonly applied on many scenarios. For example:

- Engineering: As early as 2002, Microsoft found out that by fixing 20% of reported bugs, they were able to eliminate 80% of all Errors. (However, at the same time they didn’t forget to mention that these 20% of bugs are often the nastiest, most complicated ones, and fixing them might result in new, additional problems).

- Sales: Both on a macro as well as on an individual level, 80/20 is particularly applicable to sales. 20% of customers often generate 80% of revenues, so focusing on these most important clients makes sense. Likewise, when it comes to closing deals, the decision often boils down to convincing one person (or 20% of your customer’s stakeholders).

- Strategy: In his great podcast “Masters of Scale”, Reid Hoffman and his guest Selina Tobaccowala propose to let fires burn. Focusing on the most important issues and ignoring other problems until there is no longer a way around them is just another application of the 80/20 power law.

How 80/20 works in product management

With many examples like above, people mainly associate it with efficiency and productivity, but get easily fooled by the soothing thought of only having to do 20% of the work to reap 80% of the results. This common misconception leads — particularly in the case of product development — to unfinished thoughts, horrible user experience, and in the worst case to real accidents. Diving deep into the details of the most important 20% of the backlog is the way to go.

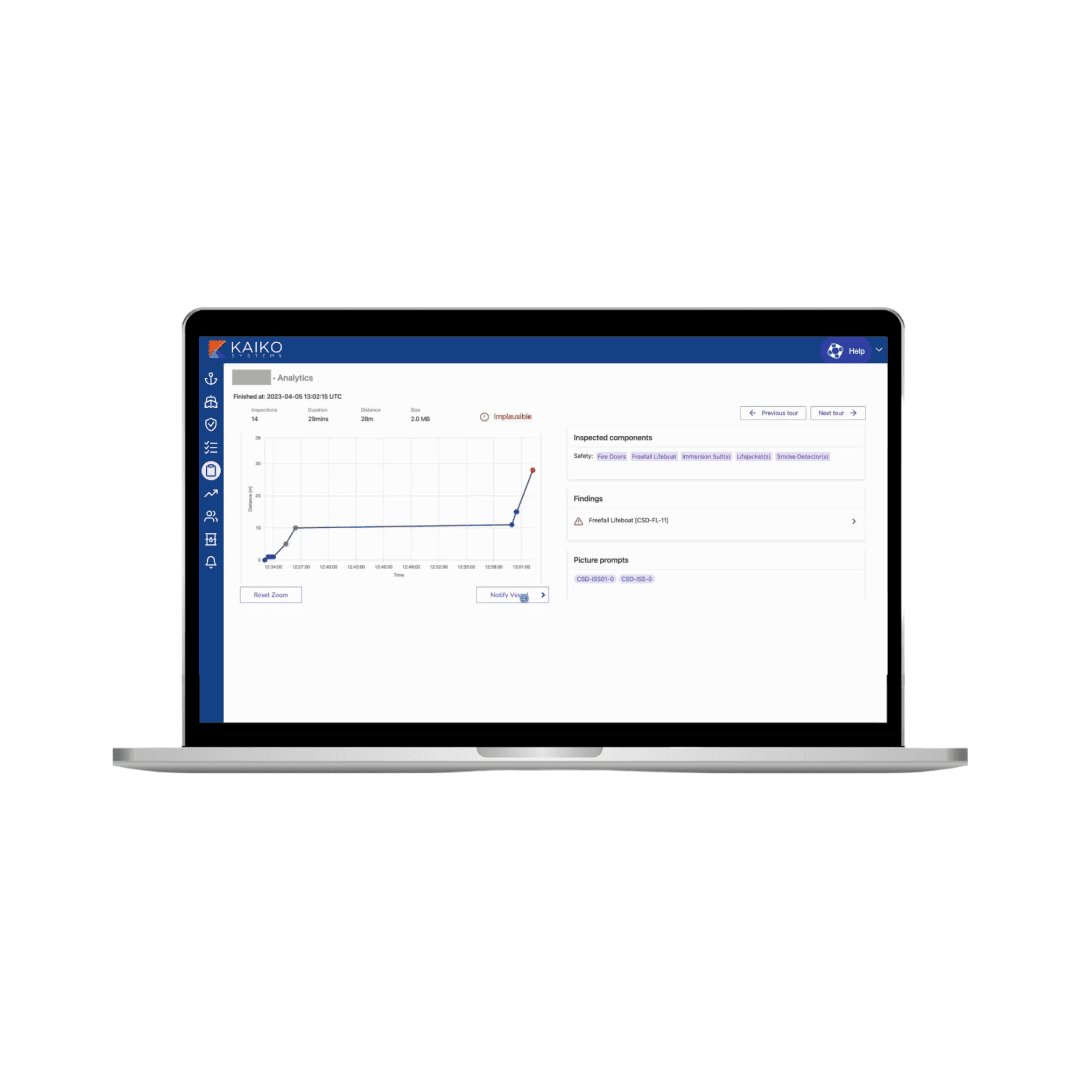

For Kaiko Systems, 80/20 holds up horizontally for product management, but not vertically. This means, focus on the 20% of features that will bring 80% of the value for a customer, and then take the details of these features very, very seriously. Every single detail of customer needs, interaction principles, edge cases needs to be considered thoroughly — in short: The depth of detail needs to be refined.

Every feature needs to consist (among other parts) of acceptance criteria, and if they are not met, the feature should not get out of the door. In a sense, after 80/20ing our way through the vast feature backlog, the development of the feature level becomes binary. It either works, or it doesn’t.

And this is especially true for B2B products. Customers expect both a simple UX similar to the mobile apps they use on a daily basis, as well as a deep understanding of their specific industry process. Bringing those expectations together requires extensive upfront thinking, conceptualizing, and testing work.

In summary, 80/20 should not be used on HOW to deliver the product. Instead, it should be used to find out WHAT to develop (breadth of options), and then get the features 100% right.